I spent this past weekend with a couple of my favorite journalists. We stayed up late discussing politics and other current events, as well as the state of print and online journalism. Then, as Friday night became Saturday morning, our thoughts naturally turned to a topic near and dear to our hearts. . . grammar!

I spent this past weekend with a couple of my favorite journalists. We stayed up late discussing politics and other current events, as well as the state of print and online journalism. Then, as Friday night became Saturday morning, our thoughts naturally turned to a topic near and dear to our hearts. . . grammar!

Yes, I know. We are geeks. It is true. And, as long as I am coming clean here, we think proper sentence structure and correct word usage are both necessary components of clear communication.

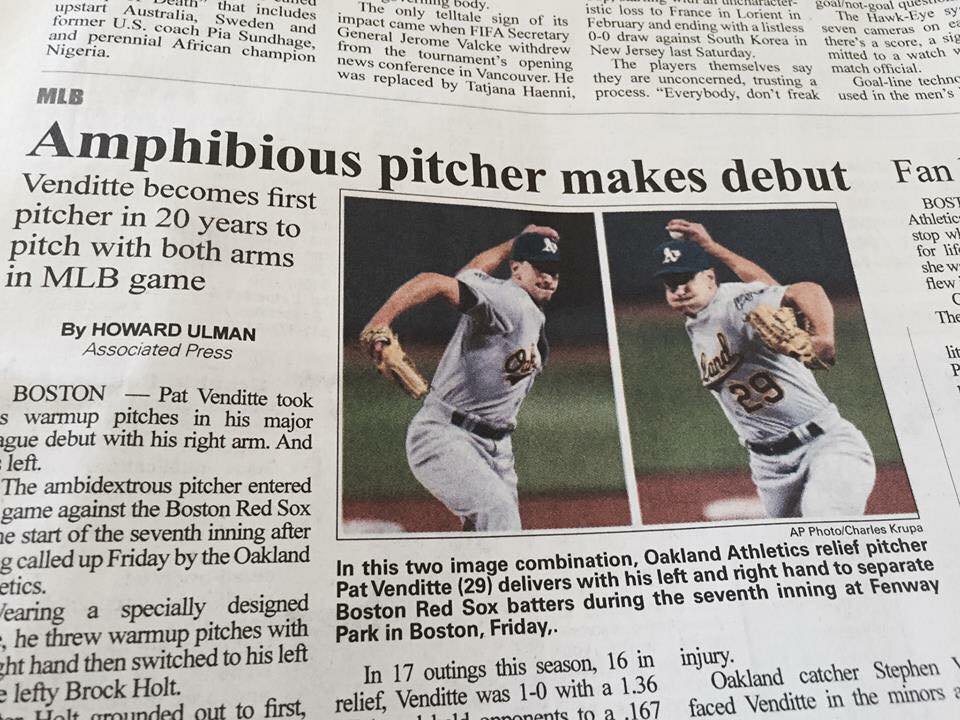

People need to understand what they are reading, especially if they read quickly. In the case of newspaper or newsletter writing, incorrect grammar slows the reader down, muddles the message, and undermines the credibility of the writer and/or news outlet. Good editors read stories with an eagle eye, a grammar handbook, their chosen stylebook, and a dictionary close at hand. If they do not (or if you do not use the same tools when self editing), your readers are forced to make sense of poor or fuzzy grammar, or guess which word you actually intended. And you may not really be saying what you mean, because even the best editor is not a mind reader. The resulting story or headline needs corrections, retractions, or some other form of cleaning up. We all have our favorite examples of this. With baseball's spring training upon us, I chuckle to recall my favorite sports headline from last season (see photo above).

I urge my speakers to be careful about their grammar as well. Even if a speech has more latitude—say, structuring it with a few em dashes or ellipses, or using a more relaxed, even colloquial vocabulary—it still needs to adhere closely to the recognized standards. Too much "artistic license" and you lose your audience. When speaking, a listener can't flip back to find the antecedent of a given pronoun, or tease out a sentence to unearth the main clause. Sentences that are complete, short, and clear are best, whether you are at the podium or conference table. Speakers generally lack proofreaders and editors, so do the job yourself. Let your ears be that extra set of eyes as you read your speech out loud. If you find you need to read a sentence a few times to make sense of it, you probably should go back and check your grammar. And for goodness' sake, if you have any question about a word, look it up! The world certainly does not need any more amphibious pitchers.

Climb ev'ry mountain

Last week I was on vacation on the Caribbean island of Nevis. If you have heard of this island at all it is likely that you know it as the birthplace of Alexander Hamilton. But Nevis is a tropical paradise, with vast beaches and their attendant beach bars, sugar mill ruins, many fine examples of Georgian Caribbean architecture. And a volcano.

Last week I was on vacation on the Caribbean island of Nevis. If you have heard of this island at all it is likely that you know it as the birthplace of Alexander Hamilton. But Nevis is a tropical paradise, with vast beaches and their attendant beach bars, sugar mill ruins, many fine examples of Georgian Caribbean architecture. And a volcano.

My dear husband talked me into climbing Nevis Peak, all 3,232 feet of it! It was not an easy hike. For one thing, tropical rain forest terrain can get extremely muddy, which is definitely a hindrance to what amounts to a vertical climb. For another thing, though I consider myself in good shape, I have never really climbed a mountain. Hiked through mountains, sure. Climbed the really steep, un-restored bits of the Great Wall east of Mutianyu. But even on the Wall there was a path of some sort, and inclines of less than 50 degrees. This was something else altogether. Very shortly into the climb, I realized three things:

1) I lacked the skills needed to do this.

2) I had to trust my guide.

3) I had to stay focused, in the moment at all times.

When it was all over my quadriceps were killing me, I was encased in mud, and my feet refused to obey. I did not say "It was fun!" like some of my fellow hikers. What I did feel was a great sense of accomplishment. I learned something new, and in the four-plus hours it took us to climb to the top (where we were in a cloud forest), then back down, I improved skills I did not even possess at the beginning. It was good to push myself outside of my comfort zone. And of course, I would have never been able to do it without my excellent guide, Reggie.

Back at our vacation villa, I took a long hot shower and tried to scrub off the bruises that I mistook for dirt--the only injuries from a slight tumble down the mountain. I realized, as the steam curled around me, easing my aching muscles, that there were many parallels to what I had just experienced and what I help my clients with on a fairly regular basis.

Many people come to me with a self-assessment that they "are in pretty good shape" speaking-wise, but lack the requisite skill and knowledge to be an expert public speaker. Or they have done pretty well so far, but are now faced with opportunities to reach far outside their comfort zones. So I, like Reggie, need to guide them through the process, instructing them to develop skills they need along the way. They need to trust me and stay focused on what we are doing. Stop judging and stay in the moment. I offer suggestions of better ways to do things, and make corrections when necessary. That is the way we all learn new techniques and improve our skills.

It can be hard to grow in this way if you are used to having easy success, or if you have reached a pinnacle of achievement. But just because you can hike for hours and do yoga like a twenty-year-old does not mean you know how to climb a mountain! You need to embrace new ways of seeing how a thing can be done and then do it. It is no coincidence that my most successful clients are those who keep moving forward. They don't stop their progress to get defensive, or offer rationalizations as to why they cling to bad speaking habits. They are in the moment, they have momentum, and continue to climb, reaching for the top!

Supreme communicators

I believe clear communication can solve many of life's problems. I applaud those who employ effective communications, even if I do not always agree with them. Disagreements are inevitable in life, but misunderstandings rooted in sloppy or lazy word choice can and should be avoided. This year's campaign season is providing us with many examples of unclear message transmittal. Sometimes this verges on the comic. But too often it makes us uneasy, eroding our confidence in the speakers. As the races tighten, I hope candidates will become more precise in what they are saying and how they are saying it.

I believe clear communication can solve many of life's problems. I applaud those who employ effective communications, even if I do not always agree with them. Disagreements are inevitable in life, but misunderstandings rooted in sloppy or lazy word choice can and should be avoided. This year's campaign season is providing us with many examples of unclear message transmittal. Sometimes this verges on the comic. But too often it makes us uneasy, eroding our confidence in the speakers. As the races tighten, I hope candidates will become more precise in what they are saying and how they are saying it.

I was sharing this view at a gathering of fellow consultants this past weekend, emphasizing the importance of preparing and practicing your message before you attempt to deliver it. This would eliminate many of the problems we are seeing on the campaign trail and debate stages. If you are ever in a comparable high-stakes situation, I hope you will take my advice: write out your talking points, then say them out loud. See if they make sense, if they actually say what you want them to, and if they flow. How comfortable are you with these words? If you are not 120% at ease with them, change 'em. Speaking in these circumstances is risky enough without the fear of lack-of-rehearsal stumble. I do not mean every utterance can be rehearsed--certainly in a debate you will be asked questions you have not anticipated (or at least we, the people, hope you are!). But your main points, the planks of your platform, should roll off your tongue eloquently and easily.

And if you are communicating largely through the written word, you still need to practice your text as if you are going to say it. Tell the story. Read your words and check them as you would if you were preparing to speak (see above). This weekend saw the untimely death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. As the media covered various aspects of his life, his legacy, each story mentioned what a brilliant writer he was. Even those who disagreed with his opinions read them with relish. Quite simply, he caught our attention and kept us engaged, which distinguishes his writing from most legal documents. Scalia's former law clerk Brian Fitzpatrick explained his secret it in an interview on NPR: "he was such a powerful writer, and I watched him write his opinions, and I figured out one of the ways that he did it was he wrote his opinions like they were speeches. He would read them aloud as he wrote them because he wanted them to be punchy like his speech was."

Precisely.

Illustration: Jurors Listening to Counsel, Supreme Court, New City Hall, New York, after Winslow Homer, 1869

courtesy National Gallery of Art

Critical communcations

Recently I witnessed some top notch communicators at work in an unexpected place while visiting a family member in the Intensive Care Unit at Medina Hospital, a member of the Cleveland Clinic health system.

Recently I witnessed some top notch communicators at work in an unexpected place while visiting a family member in the Intensive Care Unit at Medina Hospital, a member of the Cleveland Clinic health system.

You might think this an unlikely scenario for triggering professional observations about communication. But I was seriously impressed. I found myself marveling at how clearly all the hospital personnel managed to convey detailed, complex information. Often experts have difficulty with that, striking the right "tone." Explanations are either patronizingly over-simplified or pitched at too high a level for the listener. But every piece of information we were given was followed by a query regarding our comprehension, and an offer to explain again, using different words! Unlike old-school docs who would simply restate what they had said in a louder voice, trusting all would become clear if they just shouted a bit!

Our patient had some pretty scary stuff going on, and at one point the specialist needed to bring us up to speed. But before he told us what was going to happen next, he asked us to tell him what we understood her condition to be. Then he mirrored our language, finding the right level to communicate critical information. I have not spent much time in ICUs, thank goodness, but I gather from the stories of friends and from my own research that this is not the norm.

Cleveland Clinic's Center for Excellence in Healthcare Communication trains its physicians and staff to focus on relationship centered communication, rather than the old linear model still used by many healthcare providers. And the Clinic's focus on clinician-patient communications works! As family members, we had some anxiety surrounding the medical issues we were seeing, but we never felt in the dark about them. A family that understands what is going on medically is sure to provide better support.

We all know that it is critical to deliver your message clearly in times of crisis. In words that your listeners will understand. But many people still don't take the time to step up their game. I will refrain from making the blanket statement "if critical care doctors and nurses can find the time, surely you can," but I am very glad the medical professionals who staff Medina Hospital's ICU did!

Strike the pose!

I read an article today in Slate that raised some questions about the actual science behind one of the most widely viewed TED talks ever, Amy Cuddy's "Your Body Language Shapes Who You Are." I read the article with interest because I am not a huge fan of Cuddy's. When I first viewed the talk online, I did think she had interesting observations, but her argument had some holes. And then it went viral. It started being taken as Gospel Truth, and now millions of people "understand" all about body language. As with every area of expertise, a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. I hear people say, "Oh I know all about body language. I can strike a power pose." And then they do. They reach for the skies like a superhero! I point out the impracticality of attending meetings in such a position.

When I coach my clients on presenting and public speaking, I always discuss body language. I ask: What does your stance, your posture, even the tilt of your chin say about you? Or how does it get in the way of your message or the image you want to project? It is a complicated issue, because you are using several body parts, not to mention your breathing apparatus, as well as eye contact. (And that's just the non-verbals!) This degree of complexity just disappears in Cuddy's talk. She simplifies the whole process, which of course makes listeners want to believe it is true. I have to give her credit for being an excellent story teller. She has been held up as a model of someone who put together a superior TED talk. Her highly personal story provides emotional stickiness, and some scientific findings back up her thesis, for good measure.

But now the science backing up her claims has been shown to be. . .well. . . not very conclusive. And so I hope we can begin to stop swallowing her central tenet whole. A mere two minutes of engaging in an expansive pose does not, by itself, make you feel more powerful. This is too facile. Believe me, having spent the better part of my adult life around actors, it is an absolute falsehood to claim that just mimicking a posture can transform you to that degree. Not even taking on a character's posture for two hours can make you "become" the character. Actors spend weeks of rehearsal figuring out all the things we need to do before we can even come close to any sort of transformation. Not to oversimplify my objection to Cuddy's over-simplification, but the fact is each speaking situation has a different context, and the role you play varies within each context. You need to know what to do, physically, vocally and mentally, to convey strength, focus, decisiveness, collegiality, and any number of positive "leadership qualities."

If only it were as simple as striking a pose!

Misplaced passion

Now that it officially (finally) a Presidential Election Year, it's time to address the overdone, overheated rhetoric candidates are using in their primary races. So much shouting, exaggerating, trying to outdo each other while burnishing their party credentials. Making sure they have the boldest words and phrases to express their ideas and ideals. The result is a lot of hot air and posturing! It would be funny if it were not so worrisome. We can expect this sort of fervid oratory until the conventions at least. And if the most outrageous speaker of the bunch was not already getting so much media attention, I would dissect his bombastic style. But others have already done this, quite well, so I need not add to the discussion.

Now that it officially (finally) a Presidential Election Year, it's time to address the overdone, overheated rhetoric candidates are using in their primary races. So much shouting, exaggerating, trying to outdo each other while burnishing their party credentials. Making sure they have the boldest words and phrases to express their ideas and ideals. The result is a lot of hot air and posturing! It would be funny if it were not so worrisome. We can expect this sort of fervid oratory until the conventions at least. And if the most outrageous speaker of the bunch was not already getting so much media attention, I would dissect his bombastic style. But others have already done this, quite well, so I need not add to the discussion.

Instead, I look forward to the time after the nominations, when the great swath of "undecided" or unaffiliated voters will be wooed by the remaining candidates. The nominees will need to switch out their "passionate" language for a more reasoned, reasonable one. After all, you can't get people to listen to you, let alone support you, if they feel you are attacking them. I was happy to hear Shankar Vendatum on NPR discuss this very topic last month: "The problem is that the arguments that we make are the arguments that usually convince people who are like us. They don't speak the language of our opponents, and when you think about it, the only people you need to persuade are the ones who don't agree with you." Bottom line: if you are using language that does not mirror that of the people you are trying to convince, you won't connect with them. And you can't sway their opinion if there is no connection.

Politicians who try to correct their previous over-statements by reaching out to those with different views are derided as "flip-floppers." I suppose such distortion of intent is bound to happen in a 24/7 news cycle. Fortunately, the rest of us aren't under such scrutiny. We can--and should--always try to make our case using words and examples that can be understood by those we are speaking with. Shift your perspective a bit to reflect theirs. Avoid using words or images that set off alarm bells in their heads. This is not to say that you need to "play along" and "placate" those who oppose you, but going into a discussion with the intention of smacking down your opponent rarely ends well in any sort of grown-up, real-world interaction.

The display of passion can be effective, but only if judiciously employed. According to Google, "wise," "prudent," and "sensible" are all synonyms for "politic." That's good to remember in this year of 2016.

artwork: Political Drama (1914) by Robert Delaunay, courtesy National Gallery of Art

A little holiday toast

We are now in the midst of that unique time of year known as The Holiday Season. For many of us, there is a religious basis for these seasonal rituals. Others participate in the yearly festival of lights as a way to brighten dreary (and long) winter nights! But there is one thing pretty much everyone does this time of year: celebrate! And with celebrations, along with food, drink, and general merriment, come the toasts.

I wrote a longer guide to toast-making in 2011, and you can read it here if you'd like. But if you're pressed for time (and who isn't this time of year?) here are quick and easy pointers for toast-making:

1) Honor your host.

2) Toast the occasion you are celebrating (gathering of friends, workplace success, completion of another year, etc.).

3) Wish everyone the best for The New Year!

4) Raise your glass and say: "a toast to ----- " and fill in the blank with #1, #2 or #3, whichever is most important to you.

5) That's it; you're finished. Stop talking and enjoy the party.

Short and to the point. Notice that you do not talk about yourself here! Because it is not about you, and everyone seems to know this until they enter "the zone" of toast-making speechifying. You've seen it happen. So be a good friend this year and lead by example.

Happy Holidays to you and yours.

See you in 2016!

Talk less, smile more

If you, like me, have been captivated by the music of Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda's Broadway hit that is breaking all kinds of records, I am sure you have been struck by the genius of Miranda's lyrics--the wit and social commentary he injects into the historic story. When I first heard self-described "trust-fund baby" Aaron Burr tell the scrappy immigrant Hamilton to "talk less, smile more," I had to laugh. Probably any woman hearing this lyric did as well. We have all heard it so many times, usually directed toward us, as it was to Hamilton, by a member of a privileged class who is objectifying us while trying to silence us. Burr claims he is giving this advice as a friendly warning to Hamilton; in Revolutionary America, saying the wrong thing at the wrong time could get you killed. But I am guessing Miranda uses this phrase at the beginning of their relationship to set up the somewhat ambivalent, ultimately fatal nature (spoiler alert!) of their long association.

If you, like me, have been captivated by the music of Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda's Broadway hit that is breaking all kinds of records, I am sure you have been struck by the genius of Miranda's lyrics--the wit and social commentary he injects into the historic story. When I first heard self-described "trust-fund baby" Aaron Burr tell the scrappy immigrant Hamilton to "talk less, smile more," I had to laugh. Probably any woman hearing this lyric did as well. We have all heard it so many times, usually directed toward us, as it was to Hamilton, by a member of a privileged class who is objectifying us while trying to silence us. Burr claims he is giving this advice as a friendly warning to Hamilton; in Revolutionary America, saying the wrong thing at the wrong time could get you killed. But I am guessing Miranda uses this phrase at the beginning of their relationship to set up the somewhat ambivalent, ultimately fatal nature (spoiler alert!) of their long association.

Burr later uses this same phrase to describe his political strategy for wining people over without offering them much in the way of substance (and he succeeds: voters sing that he is the guy they would rather "have a beer with"). But when Hamilton's surrogate father George Washington tells him to "talk less," it is sound advice. The impetuous Hamilton has gotten himself into trouble by refusing to slow down and listen to others. Washington sees the need for Hamilton to master another skill: listening.

As a leader, Washington knew the truth about communication. It's always (at least) a two-way street. No matter how brilliant your ideas are, you cannot get your message across if you aren't willing to reach out and entertain a different viewpoint. You can't connect with people if they feel you are "talking at" them, rather than "speaking to" them.

I am not entirely sure that Alexander Hamilton learned this lesson. But as a communications coach, I believe there are many situations where talking less truly helps us make essential connections of community and communication. So, to honor our forefathers and the great American tradition of musical theatre, try it for your next big holiday gathering. You might learn more, enjoy more, connect more. And that will make you smile.

Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery

Frame and focus

My clients have been making a lot of speeches lately, and I have been helping them craft their messages. They are often sent "draft remarks" or "talking points" written by others. These documents are supposed to be for "review," but lately we have been doing wholesale rewrites. Because when you are delivering a speech, it needs to sound like you! One of "review" drafts mentioned a "favorite website of mine" that my client had never heard of. So that reference was out! If all this sounds familiar, it is; in March I wrote about why speaking in your own voice is essential for engaging your audience and maintaining credibility.

My clients have been making a lot of speeches lately, and I have been helping them craft their messages. They are often sent "draft remarks" or "talking points" written by others. These documents are supposed to be for "review," but lately we have been doing wholesale rewrites. Because when you are delivering a speech, it needs to sound like you! One of "review" drafts mentioned a "favorite website of mine" that my client had never heard of. So that reference was out! If all this sounds familiar, it is; in March I wrote about why speaking in your own voice is essential for engaging your audience and maintaining credibility. But there is another, even more fundamental aspect of content development that I am currently emphasizing. The need to keep sentences short. When you are speaking, your message goes from your mouth to the listeners' ears. And then it vanishes! No turning back to the previous page to find the sense of that sentence. Your audience is completely dependent on the clarity of your verbal delivery. So you need to guide your listeners by shaping your message for them. Focus in on your main point. Frame it clearly and stick to it. Make yourself easily understood; use active verbs and concrete images. Don't dance around the issue using complex sentences. Don't lead your audience uphill on a path going nowhere.You will lose them if your syntax, vocabulary, and logic are too hard to follow. And if you must include a list, limit the items to three. And limit your lists.

As a playwright, I am trained to listen, and reproduce, a variety of cadences, rhythms and patterns of speech. Some of my characters speak in run-on sentences. Some speak in staccato phrases. These rhythms reflect their states of mind, including clarity of thought (or lack thereof). Trained actors know how to deliver these lines so the audience understands the sense contained in the words. But actors have the benefit of rehearsal, as well as highly developed speaking skills. If my characters "ramble," or speak in highly convoluted ways, it shows they lack focus, or are arrogant, or are terribly insecure. That is fine for a character in a play, but not the persona you want to present in a professional situation!

So keep your sentences short and to the point. Strive for clarity. Focus your message. You will be amazed how much easier it is for you to "connect" with your listeners if they can actually follow what you are saying!

Venturing into the unkown

Recently I have been prepping clients for town hall-style meetings and live Q & A sessions--the type of event listed as "A conversation with the expert. . ." or "Talking to . . ." in conference programs. One of my clients said, "I want to control the conversation, even if I am being asked the questions." But he didn't want to pull that old politicians' trick of dodging the question and answering a different one instead. Right. That is never a good idea. It may seem, at the time, like an effective way to get your talking points out, but if someone is recording the exchange you will look like an idiot repeatedly, maybe even virally, ever after.

Recently I have been prepping clients for town hall-style meetings and live Q & A sessions--the type of event listed as "A conversation with the expert. . ." or "Talking to . . ." in conference programs. One of my clients said, "I want to control the conversation, even if I am being asked the questions." But he didn't want to pull that old politicians' trick of dodging the question and answering a different one instead. Right. That is never a good idea. It may seem, at the time, like an effective way to get your talking points out, but if someone is recording the exchange you will look like an idiot repeatedly, maybe even virally, ever after.

So how do you venture out into this uncharted territory? How can you ensure successful communication of your message when you are not in charge of the agenda, but responding to questions asked? It is preferable to discuss possible lines of inquiry with your moderator or interlocutor beforehand, but it's not always possible. Is there any way, short of practicing a Vulcan mind meld, to make sure your time in the spotlight offers you an opportunity to say what you need to say?

Yes. If you have done your preparation. Many people (thankfully not my clients) seem to think this is an unnecessary step. After all, you've been asked because you are the expert, so what's to prepare? You know your stuff, so you can just wing it, right? Wrong. Respect your audience. They want a little piece of your expertise, so put yourself in their shoes. Plan ahead. Plan to tell them what you find most exciting about your subject. Or discuss its timelier elements. If you can connect your subject to recent news events, so much the better. And be sure to have your best stories and examples polished and ready to be inserted into an answer early in the hour. It's not good to walk offstage and think "I really wanted to tell them about X--but it never came up." If you need to convey a particular point think of at least three ways you can weave it into answers for other likely questions.

And don't make the mistake of assuming every event of this nature will be your own personal love-fest. The moderator may think you are the best, but you could get push back from the audience. Be sure not to over-react. It is possible that the question you hear as a clear challenge to your authority may not have been meant that way at all. Since you are sitting in the speaker's "hot seat" your defensive ears could detect a menacing tone that simply isn't there. So prepare for the skeptics and always have an answer handy for the question you dread most. A real one, not a snarky aside.

Speakers often anticipate these sorts of town halls with apprehension, fearing an hour-long voyage into terra incognita. But if you take time beforehand, you can make sure you answer their questions while introducing some of your favorite talking points. And a good time will be had by all!

Learning from the best

I attend a lot of lectures and talks, and even if I am "off the clock" I can't help but judge, at least a little. How does the speaker hold my attention? To what degree (if any) is the speaker audience-centered? How does the speaker demonstrate credibility and good will? I have sat through introductions of experts with impressive credentials, who then turn out to be boring, self-centered duds. But last weekend I attended a lecture given by a master of the craft. I was visiting Union College and was lucky enough to hear Prof. Stephen M. Berk speak. A great faculty lecture is a wonderful thing, and hearing Prof. Berk talk reminded me that we can learn a lot about public speaking from such an experience. Since faculty lecturers are also teachers, they have always have a clear intention when speaking: to share their knowledge with the students. Or, in Prof. Berk's case this past weekend, with the larger college community.

I attend a lot of lectures and talks, and even if I am "off the clock" I can't help but judge, at least a little. How does the speaker hold my attention? To what degree (if any) is the speaker audience-centered? How does the speaker demonstrate credibility and good will? I have sat through introductions of experts with impressive credentials, who then turn out to be boring, self-centered duds. But last weekend I attended a lecture given by a master of the craft. I was visiting Union College and was lucky enough to hear Prof. Stephen M. Berk speak. A great faculty lecture is a wonderful thing, and hearing Prof. Berk talk reminded me that we can learn a lot about public speaking from such an experience. Since faculty lecturers are also teachers, they have always have a clear intention when speaking: to share their knowledge with the students. Or, in Prof. Berk's case this past weekend, with the larger college community.

That drive, that visceral need to share what he knows with his audience, may be the biggest factor separating a good professor from a great one. All professors are subject matter experts. They all know their stuff. But the great one goes the extra distance. She breaks down her material in steps that can be easily digested, understood. She leads her listener on a journey of understanding as she tells a story, with a beginning (introduction of concepts), middle (elaboration of these concepts), and end (wrap-up of what these concepts mean to us).

Teaching is storytelling. The listeners/students learn from the story. Prof. Berk is a history professor, so his lectures are filled with small stories, all in service to the larger over-arching story of his thesis. But what if your subject matter does not obviously lend itself to telling tales? They are there, trust me. You may need to dig to find them, but it is worth the effort. As I tell my science and tech clients: the easiest way to get people to understand what you are telling them is to construct a narrative scaffold, some structure on which to hang your facts, observations and conclusions. A list of bullet points, no matter how important or ground-breaking, is not a speech. It isn't even an explanation. And it certainly isn't engaging.

I have heard Professor Berk speak three times now, and he always manages to deliver right-sized speeches that contain the perfect blend of fact, analysis, connective story, and humor. Without notes! Some of his appeal lies in his native manner of speaking. He has a wonderful Borsht Belt rhythm to his delivery that serves him well. I have even heard him tell his "signature" story three times, but it always sounds fresh. But his is a rare talent, refined over almost five decades of teaching. Most of us will never attain his level. But his example can offer us insight into what it takes to be a great speaker: the more you do it the more you know what you need to do—in terms of preparation of material, delivery, and practice—to feel comfortable standing in the front of the room.

Illustration: "Scholars at a Lecture' by William Hogarth, courtesy National Gallery of Art

It's like talking to a mirror!

Last month I blogged about the importance of finding and using your own professional tone of voice. With everyone. All the time. I heard from several friends and colleagues that this is challenging, particularly at rigidly hierarchical workplaces. It seems they work with some people who self-identify as being "on top" who exhibit the boorish behavior of "talking down" to those below them in the org chart. And I reiterate: don't do it.

Last month I blogged about the importance of finding and using your own professional tone of voice. With everyone. All the time. I heard from several friends and colleagues that this is challenging, particularly at rigidly hierarchical workplaces. It seems they work with some people who self-identify as being "on top" who exhibit the boorish behavior of "talking down" to those below them in the org chart. And I reiterate: don't do it.

One of my friends read my blog and brought up a related topic. She said my discussion of professional tone reminded her of an old habit: emulating the tone of whoever she was talking to. I have noticed many people do this, and it is often a hard habit to break! Because it is something that we can all slip into, unconsciously, as a way of reaching out and connecting with others. This phenomenon has been studied quiet a bit: researchers call it communications accommodation theory. I looked up some academic papers to see if I could find a succinct definition, but the best one I found was in Wikipedia (and it seems pretty accurate): communication accommodation theory (CAT) was developed by Howard Giles. It posits that "when people interact they adjust their speech, their vocal patterns and their gestures, to accommodate to others". There is more to unpack here, but the gist of it is that we do this (intentionally or not) to fit in. A couple of studies that came out in psychological journals in 2010, "Alignment to Visual Speech Information" (Miller et al.), and "Imitation Improves Language Comprehension" (Adank et al.) note that this tendency often gets carried even further. They say their studies have demonstrated it is easier to understand a foreign accent if we mimic it ourselves. Of course there are disclaimers accompanying discussions of these studies: "don't try this at home!"

Research has shown we naturally gravitate to emulation or imitation of tone, even accent. But we are advised against giving into this impulse wholeheartedly. The reasoning seems to be that it could be taken as mockery of the speaker, and therefore offensive. While this may be true, it focuses too much on others' perception of you. I prefer to look at this as something you need to control because it will directly benefit you. Because when you are imitating someone else, even with noblest of intentions or instincts, you are not speaking in your own voice. You become a reflection of the person you are speaking to. For a few professionals this is desirable, and they engage in this practice intentionally. But for the rest of us? You can see that this could become one big loop of imitation, like speaking in a room full of mirrors. Which raises the question: how does a new voice get heard? How are new thoughts expressed?

Before you know it, your very honest, well-intentioned imitation has created, literally, an echo chamber of communications. This could lead to some pretty bad outcomes—much more serious than just offending someone with a bad accent. So find your voice. And use it.

****************************

Artwork:

Trees that Bring Wealth and Prosperity: Beauty

by Utagawa Hiroshige Utagawa Hiroshige

courtesy Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

Getting the tone right

"Bigger Than All of Us" at the Kennedy CenterEarlier this month I was watching actors rehearse my latest play. Well, not watching so much as listening. Carefully. I needed to make sure all my characters sounded believable. And different. Because while people who live or work together may mirror each others' speech to a certain extent, most of us speak in our own unique voices. It poses quite a challenge to the playwright to create well-rounded characters who use speech--vocabulary, sentence structure, rhythm, silence--in a variety of ways. So I have become a careful listener. And very adept at hearing the differences in tones of voice.

"Bigger Than All of Us" at the Kennedy CenterEarlier this month I was watching actors rehearse my latest play. Well, not watching so much as listening. Carefully. I needed to make sure all my characters sounded believable. And different. Because while people who live or work together may mirror each others' speech to a certain extent, most of us speak in our own unique voices. It poses quite a challenge to the playwright to create well-rounded characters who use speech--vocabulary, sentence structure, rhythm, silence--in a variety of ways. So I have become a careful listener. And very adept at hearing the differences in tones of voice.

I advise them to shift their focus and set a higher goal: to develop good habits of professional communications. Period. Find your personal professional tone, one that you can use in all circumstances. After all, you meet the same people on your way up the ladder as you do on the way down. So it's good to get in the habit of speaking with what you might think of as "office courtesy." But it won't work if it comes across as an "act" or just another business strategy. It has to be genuine and all-inclusive.

It's not as hard as you might think to cultivate such a tone. Be respectful--listen to what others have to say, make sure you are communicating clearly, and take the time to clarify. Think of it as the office variant of The Golden Rule: speak the way you would like to be spoken to. This will help take drama out of the office and put it onstage where it belongs!

Playwrights' wisdom

I have been doing a lot of writing this summer, mostly of the creative variety. And I am excited to tell you that my latest play, Bigger Than All of Us, will have its premier reading at The Kennedy Center on Labor Day, September 7. I have been up to my eyeballs in rewrites and revisions most of the summer, and am thankful for the feedback from my very able playwriting colleagues, who have supported me every step of this process. At our last meeting we were debating whether a line conveyed the "tone" I wanted, and one of my friends said, "At some point you have to trust that your words will be able to stand alone." She meant that I won't always be in the rehearsal room to make sure the director and cast know exactly what I want to convey, and how I want to convey it. I must make my precise intention crystal clear through the lines and the action of the script. My friend is right, of course. Though sometime we playwrights do "nudge" the interpretation a bit by including stage directions in our scripts to show how we hear a certain line in our heads ("sarcastically," "with suppressed glee," etc.). But we can't use that crutch too often, unless we want to identify ourselves as novices who have not learned to write very well.

I have been doing a lot of writing this summer, mostly of the creative variety. And I am excited to tell you that my latest play, Bigger Than All of Us, will have its premier reading at The Kennedy Center on Labor Day, September 7. I have been up to my eyeballs in rewrites and revisions most of the summer, and am thankful for the feedback from my very able playwriting colleagues, who have supported me every step of this process. At our last meeting we were debating whether a line conveyed the "tone" I wanted, and one of my friends said, "At some point you have to trust that your words will be able to stand alone." She meant that I won't always be in the rehearsal room to make sure the director and cast know exactly what I want to convey, and how I want to convey it. I must make my precise intention crystal clear through the lines and the action of the script. My friend is right, of course. Though sometime we playwrights do "nudge" the interpretation a bit by including stage directions in our scripts to show how we hear a certain line in our heads ("sarcastically," "with suppressed glee," etc.). But we can't use that crutch too often, unless we want to identify ourselves as novices who have not learned to write very well.

As I have been refining my script, I have also been developing a business writing workshop. My client and I are discussing this same issue: how do you convey the proper "tone?" Of course the first rule for business writing is the same first rule for all writing (whether it is a play or a speech): know your audience. Once you have the specifics of your audience in mind, you take some of the guesswork out of finding the right tone. But then you need to do what we do as playwrights, get outside your own head and listen to your message with different ears. And make no mistake: this is important for all types of writing, not just speech writing. You need to hear how your message sounds. Because when people read what you have written, they hear it in their heads. And if there is any possibility at all that your message can be misinterpreted, you need to rewrite it. Usually this means simplifying the sentence structure, and revising your word choice to use concrete language and active verbs. Sometimes it means tweaking your organization, so you clearly lead with topic sentences and choose your supporting points more judiciously. But you always need to "consider the audience" and how they will receive your message. If you write in a way they find oblique, opaque, or disrespectful for any reason, whether or not that was your intention, you will lose them.

So take a page from the playwright's script, and make sure your words clearly speak for themselves. Because you don't have the luxury of including stage directions!

Back into the frying-pan

Snapping out of my creative reverie on the ride home last Sunday, I tried to catch up on the news. As we drove south and the temperature soared, I was delighted to read an important article in The Guardian by feminist author Naomi Wolf urging young women to stop engaging in the distracting and destructive practice of vocal fry. I cheered and mentally tipped my hat to Ms. Wolf. In her article she reinforced what I have been telling clients for years. A sample: "Voice remains political at work as well. A Catalyst study found that self-advocacy skills correlate to workplace status and pay more directly than merit. In other words, speaking well is better for your career than working hard."

But in the days that followed, a backlash to her sound reasoning gathered steam. It has perplexed and dismayed me. Some read Wolf's practical advice (to strengthen your voice and so reclaim it) as silencing those voices. Well, if Wolf is a stifler of voice, then so am I. I advise all my clients and students--men and women--to kick to vocal fry habit. This gravelly sound may sound sexy or grown-up to your inner ear, but to those listening it sounds as if you a) just don't care or b) might be ill. Telling young people on their way up the career ladder to eliminate a bad habit (experts say vocal fry is usage problem, not a physiological one) seems like a smart plan to me.

I know that voice is intensely personal. It is one of the tools we use to signify to the world who we are. I work with my clients to help them polish up their existing vocal tool kit, so they can maximize their vocal potential. I would never attempt to throw out anyone's personal toolbox and replace it with something that is inauthentic. But remember: you need to use the right tool for the job.

I don't care how much you creak or fry or wallow in the gravel when you speak privately or socially. But if you are a client of mine, young or old, male or female, I will certainly help you eliminate that sound from your professional and public speaking. Because I know I am not alone in experiencing a fingernails-on-the blackboard visceral response when I hear vocal fry. Consequently, I don't/can't listen to people who do it. Which is a sure-fire way, regardless of age or gender, to silence your own voice.

Little words tell a big story

I have just finished a month teaching gifted, ambitious high school students at a summer program run by the School of Communications at American University. It is always rewarding work. I teach two classes that focus on real-time verbal communications: Speaking for Impact and The Art of the Interview (students from that class are pictured here at WUSA-9). Students work hard in our sessions to improve, and one of the areas we concentrate on is awareness and elimination of verbal tics.

As for "so:" one day 90% of the girls in my classes used it to preface many of their sentences. Only one of the boys did. Over the course of a month, I heard several speeches at the podium beginning with "so," (often paired with its good friend "OK"), and several interview questions started that way as well. That usage might be appropriate if—and only if—you are sitting in the guest chair being interviewed in a very informal setting. But when you use it to begin a speech, or before you give context or ask your question, it gives the impression that you need some kind of springboard to launch into what you have to say, which signals that you may be ill at ease. Or unprepared. Speakers might think this humanizes them (whatever that means!), but it really draws attention to their nervousness and speaker anxiety.

I am also seeing a lot of "so"s used to begin written communications from professional women who should know better! These are most often in e-mail messages and social media posts, but wherever they are, they weaken the message. It's as if the writer has some need to "back in" to the conversation, fears she does not have enough standing to simply begin. I know the women who do this would never consciously characterize their communications style this way. So why do they do it? Are they trying to be coy in order to soften a statement? Playing some kind of passive role so they can turn the tables later? Or are they simply unaware? Whatever the reason, they are not doing themselves any favors.

As I told my students, sometimes we should sweat the small stuff. Or at least be aware of the little words.

Getting the story out

I took a break from wrangling the first draft of my latest play to watch the Tony Awards last Sunday night. I was amazed by the depth and variety of the work represented onstage at Radio City Music Hall that night! And amazed that any work ever makes it to the staging stage. It is hard work mounting a new play--and a musical? Fuhgedddaboudit! It's all but impossible!

I took a break from wrangling the first draft of my latest play to watch the Tony Awards last Sunday night. I was amazed by the depth and variety of the work represented onstage at Radio City Music Hall that night! And amazed that any work ever makes it to the staging stage. It is hard work mounting a new play--and a musical? Fuhgedddaboudit! It's all but impossible!

As playwrights we know that the chances of actually seeing our work produced are slim at best. So why do we keep writing? Because the need to share stories is as old as humankind, possibly older than spoken language itself. And playwrights have stories that we are compelled to bring to life by giving them voices, faces, character names. We want the world to see/hear/feel our stories. Humans respond to stories. We use stories to bind us together in community, to help us sort out problems, lay out arguments, and celebrate our successes.

Stories can be used to teach in a deeper way, reaching a different level of understanding. We waste their power if we relegate them to the stage or story-telling venues. In TED talks, personal stories combine with research outcomes, results of experiments, or conclusions from lived experience. Speakers use them to weave narratives that compel us to keep listening. We want to know what happens: How did more children in India learn? Did Kenneth's grandfather stop sleepwalking? How does Rookie fill the teen void in popular media?

Even scientists are harnessing the power of story to clearly communicate complex ideas (I blogged about this, too. You can read it here).

We all need stories. It's no secret. Yet during our hours in workplaces and offices we are often discouraged from telling them. They are deemed fanciful, recreational, only suitable for our "off hours." Facts and data rule this world. Yes, these are important; and sometimes we must include them. But facts serve our narratives--not the other way around.

So next time you set out to write a presentation, don't just slap a bunch of numbers or bullet points up on a slide and call it good. Include some illustrative stories, a framing narrative, or a thematically significant tale. Your audience will thank you. And you'll be amazed how much better your message will stick.

What was that you said?

Yesterday many of my social media friends were posting this link to a funny story that I missed on NPR about "eggcorns. An "eggcorn", according to Merriam-Webster, is "a word or phrase that sounds like and is mistakenly used in a seemingly logical or plausible way for another word or phrase." The print version of the story lists some very funny "eggcorns." Look it over if you want a chuckle. If you live in North America I can guarantee you have heard many of these.

Yesterday many of my social media friends were posting this link to a funny story that I missed on NPR about "eggcorns. An "eggcorn", according to Merriam-Webster, is "a word or phrase that sounds like and is mistakenly used in a seemingly logical or plausible way for another word or phrase." The print version of the story lists some very funny "eggcorns." Look it over if you want a chuckle. If you live in North America I can guarantee you have heard many of these.

My favorite one was missing, though: window seal for window sill. I heard a friend say use that expression a few years ago, but I thought it was just a regional vowel substitution. Then I saw it written in lesson plans when I was substitute teaching later that spring. One of the assignments could be found, the teacher wrote, in a book on the window seal. Since this was a 6th grade English classroom with a few stuffed animals as well as books on the window sill, I hunted for a stuffed seal, hoping to find the book in question there! No seal, but I found the book—on the sill.

It's problematic when a middle school teacher makes these mistakes, but other people who should know better make them, too. And though it may be fun to laugh at friend who use language so idiosyncratically, you should probably let them know it also reveals a lot to other listeners. Those of us who are in the business of communications know that such verbal mis-steps are markers that identify the speaker as someone who is either not well-read, has not ventured too far outside a closed community, and/or is over-confident or stubborn. There may be good reasons for misunderstanding a word or phrase, but someone who wants to use it correctly and is unsure how to say it or spell it will look it up. When I gently point out "eggcorns" to students (and the occasional client) I find their willingness to self-correct correlates directly to each person's ability to master the art of dynamic communication.

But hey! If you want to keep misusing words, be my guest. There are plenty of people who will gladly rush in to fill the vacuum created by your lost credibility. After all, as Gloria Pritchett will tell you, it's a doggy-dog world out there!

Batter up!

Practice makes perfect. Theoretically, yes. But I'd like to offer this caveat: you need to practice the right thing, not just repeat mistakes. Consider this: if practice was all it took, by September, every MLB batter would be batting 1.000!

Practice makes perfect. Theoretically, yes. But I'd like to offer this caveat: you need to practice the right thing, not just repeat mistakes. Consider this: if practice was all it took, by September, every MLB batter would be batting 1.000!

This is also true when it comes to speaking. Taking advantage of many opportunities to speak (whether in a formally organized group like Toastmasters International, or in an informal workplace-based group) does indeed offer the opportunity to hone, to refine, to perfect. But you need to know what it is you are aiming for, what habits of yours need correcting, what new skills you need to acquire. The problem with peer-to-peer groups is that they may help you become more aware of what needs fixing, but they don't always offer an effective way to fix it. Often, someone will energetically advise you to "try this; it worked for me." But using tactics that worked for them may not help you at all. And the anxiety produced by this sense of failure can tie you up in even more knots.

As a speaker trainer/presentation skills consultant I spend a lot of time undoing those knots. I work with people who have been beating themselves up for years because they need to use notes, or have to let speeches "marinate" before they are fully formed. All because some "expert" (who is good at doing this himself but has no idea how to teach) proclaimed "only losers need notes" or "what's the big deal? You know your stuff, just get up there and talk about it." You can guess what I say to that! I have blogged about these issues, here and here and probably several other places as well.

If glossophobia.com is to be believed, as much as 75% of the population suffers from a fear of public speaking. So whoever is offering you advice likely had his own issues to deal with. And whatever they were, they were overcome. So hurray for him! But here's the thing—your issues are not the same. Following the same methods for fixing them is like taking someone else's pills. They might work—or they might disastrously backfire. You need your own prescription.

In speaking, as in baseball, you need to train with a coach, not just other players on the team. Sure, you need to show up on the field and practice pitching, batting, and catching, but your technique won't improve with practice alone. You need to work on the skills with someone who can recognize what you are doing wrong and offer you exercises, techniques and strategies for improvement. Then you can go out and practice. And practice, practice, practice. Ask your coach for continued help as you progress. She'll make adjustments and you'll keep working.

Stay strong! Your peers, most of whom mean well, will weigh in. Take their feedback as just that, not instruction or advice. They aren't up at bat with you, they're just watching from the bench. So smile and thank them. And then go do what you were trained to do!

Conversation stoppers

My clients have recently been asking me about interrupting and over-talking. The fact is, everyone interrupts. It is not longer just "what rude people do"—if, indeed, it ever was! So it's time for all of us to stop being so reflexively judgmental, and look at intentions and outcomes.

My clients have recently been asking me about interrupting and over-talking. The fact is, everyone interrupts. It is not longer just "what rude people do"—if, indeed, it ever was! So it's time for all of us to stop being so reflexively judgmental, and look at intentions and outcomes.

Some peopIe, in a misguided attempt to "stick to the agenda" wield the "no interrupting" cudgel more forcefully than any preschool teacher ever dared. I won't take time here to explain that this action in itself can be disruptive, or analyze the importance of perceived power to those who still cling to this idea. I would just like to ask them to calm down a bit, get off their high horses, and note that linguists and anthropologists have been pointing out for years that communication styles vary across cultures. What one group sees as incredibly rude over-talking, another sees as necessary bonding activity. Deborah Tannen's landmark 1990 book, You Just Don't Understand, is remembered for shedding light on the different conversational styles between men and women. I read it back when I was a Midwestern transplant to NYC, and what struck me most was her analysis of the influences of geography and related cultural norms. Now I live in Virginia, where I am in meetings with those who pride themselves on their "gentility" while speaking. As I look around the room, I find I am not alone in hoping they will soon get to the point.

The interruptions will always be with us. Because unless you are living in a homogeneous world, those at the table will not share the same perspective on what is acceptable. Many see interrupting as a positive thing, a chance to show enthusiasm, as in "Yes! what a great idea! I agree!" Others only see someone grabbing the conversation and commanding the floor. But let's step back. Are these all, really, conversation-stopping "derailers?" The type of interruption that serves no purpose other than to glorify the speaker? In a recent piece for his very clever advice column, writer David Eddie points out the differences between these odious high-jackers of conversation and "garden-variety interrupters," offering some amusing (and probably very effective) ways to deal with them.

I am no advice columnist, but I will urge you all—friends, clients, and colleagues—to look at why interruptions take place and where they lead. Unless they are total communications disrupters like Eddie's derailers, it is often prudent to go with the flow and let those interruptions happen. Of course you need to keep the conversation on track, but think of yourself more as the school crossing guard, making sure everyone gets to their destinations safely, rather than the traffic cop who issues tickets for (sometimes minor) infractions.