Welcome sign at our launch partyThis month I've been busy helping launch Pipeline Playwrights, a new theatre company that three playwright friends and I have started. I am also getting my third-to-latest play, Becoming Calvin, ready for publication, and planning for a staged reading of my newest comedy, A Very Present Presence. Spending time in the theatre, with its practical problem-solving and newly-created imaginary worlds, has been a welcome respite from current events. And I wonder if we were somehow prescient in the summer when we crafted Pipeline Playwright's mission statement: "Our goal is to communicate individual truths that transcend the separate self and bind us together in community." This concept of community has since become, for many of us, a crucial component of moving forward and getting on with life.

Welcome sign at our launch partyThis month I've been busy helping launch Pipeline Playwrights, a new theatre company that three playwright friends and I have started. I am also getting my third-to-latest play, Becoming Calvin, ready for publication, and planning for a staged reading of my newest comedy, A Very Present Presence. Spending time in the theatre, with its practical problem-solving and newly-created imaginary worlds, has been a welcome respite from current events. And I wonder if we were somehow prescient in the summer when we crafted Pipeline Playwright's mission statement: "Our goal is to communicate individual truths that transcend the separate self and bind us together in community." This concept of community has since become, for many of us, a crucial component of moving forward and getting on with life.

Community is the essence of theatre. Yet writing a play, like writing a speech, is a solitary act. In both cases the what of the writing is your vision or message. But why, exactly are you writing? Because you need, on some level, to get thoughts out of your head and offer them up for others to see, hear, share. So far, so good. But once written, how does your message reach your audience? Working as a director I know that actors best convey the playwright's intention through action. And the same holds true when you speak: you need to find the action. That may sound a bit daunting, but it shouldn't be, because speaking is, by its very nature, a physical activity! Think about it: whenever you stand up (or sit down) to speak publicly, you engage your body in getting your message out there. You're like the actor who gets the playwright's message across by acting--not in the sense of "pretending," but "engaging in action."

Making these connections is why I love working as a Communications Artist! It allows me to help my clients put community into every communication.

Speaking privately in public

With some reluctance I listened to Donald Trump's inaugural address last week. His speaking style has been like fingernails-on-a-blackboard to me since he began campaigning. But as a speaking coach, I knew I had to. So I livestreamed the speech on PBS last Friday, hoping to gain some insight into why his communication style has resonated with so many people. This speech was a bit more formal than his usual, but it still had elements of his trademark manner. I was reminded why he is such a gift to comedians, with confusing syntax, simplistic vocabulary, and overall crassness. There is nothing at all leader-like about the way he presents himself.

And yet I know that is what his voters say they responded to during the campaign: his complete and utter upending of The Rules, which extends to grammar, it seems. But I still was not sure what exactly it was about his speaking style that won them over.

Then it dawned on me. He speaks publicly but does not engage in public speaking. He is very much in private speech mode. And he's not alone is using private speech in a public place; it's an easy trap to fall into. We all know, of course, that when you're speaking at a podium it's public speech, but so is the meeting in the board room. Even most of what you engage in at the worksplace, though it may be informal, is still public if you don't know your conversation partners extremely (I-can-trust-you-not-to-tell-anyone) well. Public speech tends to rely as much on transactional as relational speech. For example, you develop relationships with co-workers to get things done. In private speech, relationship is paramount; transactions are often absent. It is the act of connecting that gives the conversation meaning. Subtext is all in private speech. So when we know people well and have bonds of trust with them, we can be sloppy in our word choice, not finish sentences, say "you know what I mean"--and trust that they probably do! With intimacy we assume an understanding.

That is what Donald Trump's speech conveys. (John McWhorter shares a similar conculsion in his op-ed in the New York Times.) Though Trump is not personally close to his audience, his mode of speech implies intimacy to them. He uses pseudo-private speech (which his supporters call "authenticity") as his mode of delivery. It does nothing for me; I find the casual tone, lack of preparation and general thoughtless disrespectful in the extreme. BUT I can see how it might appeal to others who identify as the "forgotten people." Thinking the leader of our nation sees you as one of his buds must be very empowering.

When most of us use private speech, talking to those we know well, there is opportunity to clarify misunderstandings. And when friends say things we don't always agree with, we know them well enough to judge what they really believe and will act upon. If we're unsure, we ask. That will never be possible with Donald Trump. We will never know what he truly believes. His "just plain talk" approach worked to get him elected, yes. But one of these days those who voted for him will find out that his "honest authneticity" was just a trick conveyed by his undisciplined speaking style. When they realize they never really knew him, that he was the friend who got all the benefits, I would guess that many of them will see his "relatability" as a huge con.

Only connect

It's a new year and I am getting lots of calls from folks who have resolved to improve their public speaking. My callers have a variety of needs: conferences to present for, remarks to make, pitches to deliver. If you have any of these coming up you may be doing this right now: writing a draft, right-sizing it to give your audience just enough (but not too much) info. Then you'll shape it using the classic beginning-middle-end narrative structure. You'll remember to use story effectively both as a framing device and for specific examples. And when you finish you'll be all set, right?

It's a new year and I am getting lots of calls from folks who have resolved to improve their public speaking. My callers have a variety of needs: conferences to present for, remarks to make, pitches to deliver. If you have any of these coming up you may be doing this right now: writing a draft, right-sizing it to give your audience just enough (but not too much) info. Then you'll shape it using the classic beginning-middle-end narrative structure. You'll remember to use story effectively both as a framing device and for specific examples. And when you finish you'll be all set, right?

Well, no. Mastering your content is only half of it. Communicating your message depends as much, if not more, on your delivery. Time and again I have seen people who fail because they can't connect with their listeners. It's not just picking the right words and arranging them the right way that makes such connection possible. After all, you're not submitting a memo or a report. You're communicating through speech so you and your listeners can connect directly. You need to own what you are saying. And feel compelled to communicate it. Only then can others feel your enthusiasm, disappointment, or whatever underlying human emotion has led you to engage in this inherently scary act of public speaking.

I know, I know. I've heard it, too: it's best to "speak from the heart" (i.e. without a prepared text). That way you naturally connect with your audience. WRONG! When speakers neglect preparation to avoid sounding "scripted" they end up with a mess of underdeveloped points and random anecdotes, just wasting the listeners' time.

The truth is, to be a great speaker you need clear, powerful content and emotionally resonant delivery. It takes time to work on both parts of effective messaging, but what's the alternative? Being "fine" (a.k.a. boring and instantly forgettable)? Not getting your message across clearly? Feeling terrified because you can't call up those reserves of "passion" you were depending on, and find yourself staring in horror at three bullet points as your only lifeline? That's what makes people fear public speaking more than death itself.

You can do better. Here's hoping 2017 will be the year you start making those crucial communications connections!

A holiday wish list

If I were able to give gifts to each of you, you'd find these under your tree (or wherever you find your holiday surprises): wishes to help you all become terrific speakers in 2017.

If I were able to give gifts to each of you, you'd find these under your tree (or wherever you find your holiday surprises): wishes to help you all become terrific speakers in 2017.

I wish for you:

- cooperative contacts (or research assistants) who will give you specific details about your audience: who are they? why do they want/need to hear from you? why do they want to hear it now?

- mental space to fully prepare what you are going to say prior to the day before you have to say it.

- an internal outlining and right-sizing alert system so you will sense when you are going on too long, getting off track, or giving more information than your audience can digest.

- the knowledge that classic story-telling models are best, because audiences can follow a narrative structure: Beginning (introduction and scene-setting); Middle (three to four--NO MORE--points); End (wrap up and conclusion).

- awareness of the physicality of the act of speaking to keep you from getting stuck in your mental cul-de-sac where that nagging negative voice lives.

- realization that it's about the message, not about you, freeing you from obsessing over your hair, shoes, or whatever your Achilles' heel is.

If you get even a couple of these in your stocking, your performance as a speaker will improve immensely . . . and soon, too. If you don't, you can always give me a call. I'll probably have something left in my gift closet!

Thanksgiving in the aftermath

Thanksgiving--a day of food, family and fellowship. It offers us, just before the Holiday Crazies begin, a glorious day to kick back, relax, and count our blessings. In the past, I have reflected in this space on what I am personally thankful for. My list covers a lot of ground, from supportive friends and family to the brilliant comic Sarah Silverman.

Thanksgiving--a day of food, family and fellowship. It offers us, just before the Holiday Crazies begin, a glorious day to kick back, relax, and count our blessings. In the past, I have reflected in this space on what I am personally thankful for. My list covers a lot of ground, from supportive friends and family to the brilliant comic Sarah Silverman.

This year, however, I offer a different message to those of you venturing outside your comfort zone, taking that real (or metaphorical) journey over the river and through the woods. We have all been bruised by the grueling election season and its immediate aftermath. So as our national holiday approaches, we would do well to look around and ask how we can put ourselves, our families and our communities back together. Let's take a simple first step and listen, really listen, to one another. Now don't get me wrong--I am not advocating acquiescence or amnesia. But I am suggesting it might be best to wait until after the pie is served to point out Aunt Tammy's rhetoric of racism, Cousin Fred's sexism, or neighbor Abigail's elitism. Because we do need to root out language that excludes and divides. At the same time, it is important to find common ground with those who have different perspectives. We must do that if we want to continue The American Experiment we celebrate at Thanksgiving. So I propose that as we mash the potatoes, sit down to the turkey, watch the parade, or enjoy the game, we actually try to listen to each other with open ears and open hearts. Because like the route to Grandmother's house, the road to real communication may be a long one, but it is never a one-way street.

Boxed In

Picture this: you're facing a room full of strangers, telling them about something you understand inside out, when suddenly you see blank looks on too many faces, and wonder if you started speaking a foreign language. Or, just after you have confidently delivered your speech, you find out from the questions asked that people did not get what you were saying, not one bit. Sound familiar? It happens to most of us somewhere along the line.

Picture this: you're facing a room full of strangers, telling them about something you understand inside out, when suddenly you see blank looks on too many faces, and wonder if you started speaking a foreign language. Or, just after you have confidently delivered your speech, you find out from the questions asked that people did not get what you were saying, not one bit. Sound familiar? It happens to most of us somewhere along the line.

When we really know our stuff we run that risk even more. Which is why being an expert in your field does not necessarily mean you're the best person to speak about your topic. Remember those speeches you've heard from esteemed experts or cutting-edge innovators who lost you after "good morning?" As listeners, such an experience represents a lost opportunity for learning at best, and a complete waste of time at worst. Yet when the tables are turned and we are the ones speaking, how do we regard these speech fails? All too often we blame our audience for not being smart or attentive enough to cherish the pearls of wisdom we are throwing before them. That is the completely wrong approach.

Wherever you are speaking--a classroom, an auditorium, or a meeting room-- your primary objective is to connect. Always. The verb may vary: share, teach, elucidate--even, perhaps, persuade. But remember you cannot convince anyone of anything until you have made a deep, real connection first! And that means taking a step back. Getting out of the weeds. You may be immersed in your topic and quite excited about what you have to share, but unless you are speaking a language your audience understands you won't connect.

We are facing some pretty huge problems these days, many of them compounded by the fact that not only do people not understand, they have given up trying to understand. The big, complicated concepts that drive science, economics, and politics shaping our daily lives will certainly affect the future of our communities, our country, and our planet. But many don't have the interest or desire to begin to understand them. There are many reasons for this, but one thing I have seen over and over is the inability of experts to effectively explain these concepts to non-experts. If people don't understand the larger relationships between various forms of energy usage and climate change, for example, maybe it's because no one has taken time to explain it in way they understand. Life moves pretty fast these days (thanks, Ferris!) and if you don't make an effort to connect, people feel disrespected. Then it's Bye Felicia.

And there you are, one step closer to having your great solution to the world's problems shot down by ignorant funders, defeated by a misinformed electorate, or otherwise sabotaged by people you might see as "just plain dumb." But you have to take responsibility as a speaker. No one can read your mind, and if you need to connect the dots for them, that is what you do. Step outside yourself and see what might be complicated or hard to comprehend. Ask someone to help. Someone who is not an expert in the way you are. Then break it down. And practice. Putting a reminder in the notes section of your PowerPoint is not enough. You need to make a plan and "bake it into" your presentation. If you wait for Q & A at the end to gauge audience understanding, you run the risk of sending too many listeners to their happy place along the way. And that's not a risk any of us can afford.

So step outside of the box you've put yourself in. The one where you're comfortable talking to people who already understand what you mean. And try to connect with others out there in the wide, wide world.

Toxic weeds

As someone whose whole professional life has to do with words and what we communicate through them, underneath them, and in between them, I have had many thoughts "communication" in the final weeks of this presidential election. I qualify the term because communication theory posits a loop: speaker-message-listener-feedback-speaker, etc. What we have seen from Donald Trump has been like broadcasting--in its original 18th century usage, "seeds sown by scattering." Accusations, overstatements and generalizations are thrown to the winds, and, with nothing to tie them down to reality, these seeds of half-baked ideas float about until they land in some sort of soil. If it is not hospitable they wither and die, but if they find fertile soil, they take root and grow into toxic weeds that threaten to overrun anything near them. I have a weed like that in my backyard. It winds through my neighbors' fence into our space. We call it the "evil weed" And, like Donald, it always comes back no matter how often we try to yank it out. Because the roots are not something we control.

I have been thinking a lot about the depths to which our political discourse has fallen this cycle. Bullying tactics have become more and more normalized as we slog on toward November. They have reached a fever pitch in the past ten days, and I fear that our sense of what constitutes bullying and why it is so bad for us may be permanently warped. When Donald stands in front of the press and public and says with a straight face "It was just words. It didn't mean anything," it makes my blood boil. Of course words have meaning! I have blogged before about this facile excuse for bad behavior. Every word has an intention behind it (unless your brain has become disengaged from your mouth--which almost seems to be Trump's defense. But that can't be right. Who would vote for a candidate who doesn't think before he speaks. Oh. Maybe that is what they mean by "authenticity"?!?) And, contrary to what his campaign tells us, the concept that bullying is wrong has not just been rolled out this October to thwart Donald. In January 2104 I wrote about the need to see language as a tool that can easily be weaponized; at that time, even the NYPD recognized that fact.

Like so many people, I am weary of this election charade. The daily posturing, name-calling, hate-filled language coming from the Trump camp is something many of us have been working to eradicate for years. It is invading our space, like my backyard's evil weed, which I will keep pulling out and cutting back. And someday I will either weaken it so much that it can no longer thrive, or I will have to do something I have resisted thus far, and go ask the neighbors to help. They may not want to eradicate it (they seem to find it attractive), so we will compromise and work toward a mutually beneficial solution. That's what grown-ups in a civil society do.

Comfortable in her own skin

One thing was crystal clear to me as I watched the first presidential debate on September 26th: only one of the candidates was comfortable in her own skin! Hillary kept cool, and expressed her feelings with a secret smile, which seemed to serve as protective armor (the "go to your happy place" technique most women are all too familiar with), and an expression of genuine glee ("all that studying paid off!"). She must have decided to control what she could, and not waste energy worrying about anything she couldn't--like her unpredictable opponent. She maintained her composure and spoke in a relaxed tone of voice, and looked like she felt centered, grounded and as calm as possibe under the glare of those lights. She had, as we say in acting, an objective: something you want to/need to accomplish in the course of a given scene. She made reaching that objective her goal--regardless of her obstacle.

Donald, on the other hand, reminded me of insecure beginning acting students who flash "aren't I great?" looks at the instructor and classmates because they know they have no idea what to do. But they hope their false confidence can hoodwink the audience. The technical term for such a person is "show-off." I think Donald falls into that category, though he thinks of himself as a showman. His "technique" consists of riffing off what his audience gives him. Since he has so little in the way of a coherent message, he depends on their response to guide him, claiming that "off the cuff" is more authentic. (You know what I say about that.) That approach might work for a well-trained improv performer, but not Donald. He's a mediocre showman, at best. And when he is out on a tightrope without the net of audience cheers, he has no center to help him keep his balance. His energy is all outward-focused; he pushes his message at his audience. And when he can't tell if it's connecting, as we saw in the first debate, he has no inner resources to fall back on. Because there is no real objective beyond basking in the crowd's adulation.

The next debate on October 9th is town hall-style. This will be fascinating because Donald will assume he can nail it. But this will be no rally of Trumpers. And it will be moderated. The intimate setting will reveal who is most comfortable in their own skin, who has integrated their message into their very being. Barack Obama, I recall, did an extremely good job of playing to the audience in his 2008 Town Hall. That is where I first noticed he was ambidextrously handling the microphone, so he could gesture inclusively to the entire audience surrounding him. Not an easy thing to do, and one that would not even be on most candidate's radar. But non-verbal connection is important. So if Hillary can keep up her relaxed focus, she'll have an even better time in that informal setting than she did behind the podium. And Donald? He'll shout and stomp, rail and rage. He'd better be careful, though, or he might fall off the tightrope!

Tone policing: Vinegar vs. Honey

I could write a book on how power has been wielded against me in this way by those who felt my speech threatened their privileged worldview. So much that they were justified in silencing me. And this has not been just my experience! Our screens are exploding with examples of that behavior now, on TV, on social media, as well as in the press. Black Lives Matter activists are being told, as they express their quite justified anger, that they won't be listened to until they can "be more reasonable." Transgender allies are being shut out of conversations because they dare to raise their voices in protest of ridiculous "bathroom bills" or police brutality.

Then there is the other side of the coin. The spurious argument about infringement of free speech rights. Supporters of the outlandish candidate for president spew repugnant falsehoods, then turn around and accuse those attempting to engage in civil dialogue of trampling their free speech rights. But calling someone out on hate speech is never wrong. Bigots, racists, homophobes and haters of all kinds do not see it this way; their blindness on the issue is a large part of their problem.

No, shutting down the hate is not tone policing. Tone policing hinges on power imbalance. Assumptions of superiority couple with the fear of losing undeserved privilege and result in reflexive silencing of those who would challenge that privilege. So when the marginalized lash out at their oppressors, the oppressors duck the issue by saying "I can't talk to you; you're too upset!" or "I can't hear what she is saying because she is too shrill!" Or, my personal favorite, the dismissal disguised as "friendly advice" from a gatekeeping stranger: "you'll catch more flies with honey than with vinegar, sweetie."

All these arguments are spurious. People who are angry need to be listened to, not ignored because they aren't using your preferred vocabulary with the correct tone at an acceptable time. Anyone who has successfully raised a child can tell you that! The sooner you address their grievance, the better for all of us. It is a problem-solving short-cut, the most effective one anybody has come up with. So even if the only strife you encounter is in your home or office, be aware that silencing people in this way will only make things worse.

Oh, and by the way--I just had to trap a bunch of fruit flies hanging around my kitchen and guess what? My jar of vinegar caught dozens. And the honey? Not a one!

True trickiness of tone

So once again I have been deep in the weeds examining the crucial role played by tone in interpersonal communications. What subtext or hidden intention does a character reveal to other characters and to the audience by her particular tone? How do I, as a playwright, convey that through the words I chose to have her speak? And, extrapolating to real life, what does a particular speaker's tone tell us, as listeners? And when we speak, why do we need to be mindful of it?

We all know that how people say what they say colors the meaning. We process words differently depending on what we perceive the speaker's underlying intention to be. And by the way, it seems dogs do this as well (so stop trying to fool poor Fido by crooning "sweet stupid dog" as you pet him).

But there is also unconscious bias on the part of the listener. People often react the way they are predisposed to, regardless of the words said and the way they are delivered. The speaker may be intending to convey something on an entirely different level with her words than she is signalling with her tone (which is where the concept of subtext--or what is said beneath the text--comes in). Then on top of that, the listener brings her own bias to bear, probably without really realizing it.

This potential for misunderstanding and misperception is a goldmine for comedy writers. I have been utilizing this fact of human nature in my plays. And Tina Fey and her team put it to good use in The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt (check it out if you haven't. It's nominated for 11 Emmy Awards). Kimmy chooses to see the best in people. So when she turns to her friends for support and comfort, she is often satisfied by whatever they say, ignoring the fact that their words may not specifically address her problem. They respond, showing they are aware she has a need, and that is good enough for her. It is the incongruity of the situation--the disconnect between apparent message sent and message received--that makes us laugh!

In real life, though, these layer of meaning can cause confusion, or worse. And sometimes it isn't worth your time or effort to sort out what an off-hand remark by a colleague might have meant. But the more you listen carefully--to yourself and others--the more you can learn about messages and the intention underneath. In many professional/public situations this is a valuable skill to possess. In your personal life, maybe not so much. Our private interactions are so subtext-heavy that words very often take a backseat to tone. And if you're like Kimmy, the fact that someone sees you have a problem--and is addressing it, however vaguely--is often enough to convince you that they care.

************

photo from A Very Present Presence at The Kennedy Center, Sept 5, 2106

Being politically "authentic"

If you've read my blog before you may remember this entry or this one where I share my thoughts on using "authenticity" as an excuse for sloppiness, laziness, or pretense. So I was happy to read Mark Thompson's op-ed in yesterday' s New York Times, Trump and the Dark History of Straight Talk. He says Trump is actually one in a long line of political types who use anti-rhetoric (his "telling it like it is" strategy) as a way to prove he is the anti-establishment candidate. But Thompson points out that Trump's "authenticity" is not so very authentic after all: "The quality to which every anti-rhetorician aspires is authenticity. But there is a big difference between proclaiming your authenticity and actually being true to yourself and the facts. So let me use a different term: authenticism, for the philosophical and rhetorical strategy of emphasizing the “authentic” above all."

Donald Trump is playing at being "authentic," but it is a false authenticity. He is quite the showman, however, and his show is playing well with the thousands of voters who flock to his extravaganzas—I mean, his rallies. But scratch the surface, and his authenticity falls away. We see this in his recent imitation of a weathervane when it comes to immigration. His earlier tough talk was just a ploy to knock off primary rivals.

Thompson says Hillary Clinton is the complete opposite of Trump, rhetorically. He calls her the "technocrat's technocrat." I take this to mean she is too "in the weeds" in her speeches. She gives too much detail, is too strategic, too cerebral. She appeals to voter's heads but not their hearts. I am not sure this is true of all her speeches, and certainly the content of many of her speeches doesn't support this assertion (the Reno speech was full of feeling). But her delivery does get in the way of making a connection with her listeners. Which frustrates me no end.

Like much of America, I have been a Hillary-watcher for years. I definitely think I could offer her some help. The secret to connecting with listeners is exactly what I teach: how to communicate your authentic presence; how to speak in your own voice. Even if you are an introvert I can give you strategies for standing up in front of rooms of 25 or 2500 to confidently share your message. The key is using your inner strength to draw your audience toward you, rather than pushing your message at them (which is a hallmark of Trumpian "authenticism").

But discovering how to communicate with such authenticity takes time and self-study. And political campaigns are reluctant to have candidates give me either. When I have had success, it is because candidates have been acutely aware of their need to connect more fully with voters and have sought me out. They have made the time, in spite of grumbling from staffers that they didn't need this training, not really, because they were "fine" on the stump. Working with me (or any speaking coach, for that matter) does not guarantee victory. No single element in a campaign does. But even when my clients lost, they won more votes than they expected.

Until campaigns realize that helping a candidate communicate with true authenticity is an important skill to develop, we may be stuck with campaign as entertainment vs. campaign as lecture. Let's hope the party powers-that-be have this realization soon, or we could all come to dread this peculiarly American quadrennial ritual.

****photo inspired by Emily Dickinson's poem "I'm Nobody"

Want to move up? Listen down

Lining up to hear the candidate. Hot summer, 2016 This political season I have been watching, cringing, and shaking my head. I find a huuuuge gulf between what I think of as leadership and what certain segments of the electorate and media seem to think it is. For one thing, it has become abundantly clear that Donald Trump is not a good listener. Never has been, never will be. And he's OK with that. This should be a red flag for anyone thinking about voting for him. It is disastrous for a company, organization or any sort of coalition when the person in charge refuses to listen to other points of view. Imagine how catastrophic it would be to elect a head of state who does not possess the skill--or even desire--to be a good listener!

Lining up to hear the candidate. Hot summer, 2016 This political season I have been watching, cringing, and shaking my head. I find a huuuuge gulf between what I think of as leadership and what certain segments of the electorate and media seem to think it is. For one thing, it has become abundantly clear that Donald Trump is not a good listener. Never has been, never will be. And he's OK with that. This should be a red flag for anyone thinking about voting for him. It is disastrous for a company, organization or any sort of coalition when the person in charge refuses to listen to other points of view. Imagine how catastrophic it would be to elect a head of state who does not possess the skill--or even desire--to be a good listener!

Here is a blog I wrote in January, 2014 that unpacks why it is critical for a leader to have good listening skills. Enjoy.

Last week, while trying to solve some communications problems specific to clients in leadership roles, I looked to Adam Bryant's "Corner Office" interview with Penny Pritzker in the New York Times, "On Hearing the Whole Story." Pritzker, a highly successful business leader in the real estate, hospitality, and financial services industries, is currently serving as Secretary of Commerce. She answered Bryant's question about improving her leadership over the years this way:

"Probably the biggest mistakes I’ve made were when I wasn’t listening carefully enough. Sometimes you need help with that. I have often said to my closest advisers that your job isn’t just to tell me what you think, but you also have to get in my face and make sure I heard you. It’s hard to deliver bad news, and part of leadership is giving people permission to give you bad news, and making sure you really hear it."

The thing that struck me was how much humility is packed in that statement. And the acknowledgement that true leadership means a willingness to deal with uncertain, or even negative, feedback. A reminder that when you are a leader it is not about you, but about the shared goal of the stakeholders in your venture. If your staff or team is reluctant to give you bad news, then how can you really find our what is going on? Their job in not to please you, but to give you the information you need.

As Shanti Atkins, President and CSO of Navex Global, said in Bryant's January 2nd column: "Even now I like to have people around me who will disagree with me and who will tell me when they think I’m wrong or something is a terrible idea. If I get the feeling I have people around me who are managing up, I get very nervous. I just instantly start wondering, 'What’s actually happening and why can’t you give me more of a balanced picture?' ”

We all need to be ready to really hear what employees, co-workers, even family members, have to say--especially when it is something we may not want to hear! Let's resolve to be better--and more open--listeners this year. Mindfully practicing our listening skills will improve every facet of our lives, not just the bottom line.

It sure is sticky!

It is hot hot hot here in Northern Virginia these days! When I get up in the morning I dread hearing it's going to be "sticky." Ugh! It's not so bad if I have scheduled a "writing day" indoors, but if I am out metroing to client sites, "sticky" just about does me in.

It is hot hot hot here in Northern Virginia these days! When I get up in the morning I dread hearing it's going to be "sticky." Ugh! It's not so bad if I have scheduled a "writing day" indoors, but if I am out metroing to client sites, "sticky" just about does me in.

But "stickiness" can be a positive thing: in verbal communication it is something we strive for--making your message stick. Studies show audience members recall on average less than a quarter of what they hear at any speech, meeting, conference call, etc. With those odds, all of us who speak need to do everything we can to ensure our message is memorable.

I know, I know, everyone says this. But just how do you go about writing a speech, or even crafting talking points, that will stick? Many of us take shortcuts here, believing whatever we say has great value. Because we all overestimate the universal value of our insights, our thoughts and musings. And so we forget to put ourselves in anyone else's shoes and ask--what's in it for them?

There are many resources online to aid in your creation of sticky content, and many consultants like me who would be happy to help! But I'll give you two big tips now. The first thing you absolutely need to do is ask yourself: how can I relate to my audience/listeners? For this you need to do some research and find out who your audience is, and why you are speaking to them about this specific topic at this particular time. Then decide on stories you can share, and vivid, concrete examples you can give that will capture their imaginations and put them in the room with you. Establish that connection right off the bat, and they are more likely to stay aboard your train of thought.

Once you've hooked them this way, make sure you don't lose them: write for the ear, not the eye. Short sentences with active verbs. No jargon. Cut those dependent clauses and make sure your pronouns have antecedents. Be clear, above all.

If you can master these two elements of messaging, you may find yourself in a sticky situation. But a good sticky: like honey, not humidity!

Cool fun in the summer

I have been teaching some really terrific high school students who have come to American University for its Discover the World of Communications summer program. This blog post shares some of the video clips I have used reinforce and illustrate my teaching. Feel free to skip my musings, but watch these videos! You will be entertained by the first and fourth links below, enlightened by the middle two.

I have been teaching some really terrific high school students who have come to American University for its Discover the World of Communications summer program. This blog post shares some of the video clips I have used reinforce and illustrate my teaching. Feel free to skip my musings, but watch these videos! You will be entertained by the first and fourth links below, enlightened by the middle two.

This is my eleventh summer teaching Speaking for Impact, where students learn to find their inner presence and embrace it as a way to quell anxiety and project authority. I give them much of the theory and many of the exercises I share with my adult clients, because the fundamental problems of nervousness, lack of confidence, and confusion about preparation are the same.

But the teaching tools I use are different: we watch a lot of video! There are many excellent speeches available online that we can learn from. Commencement speeches are great, of course, but there is a virtual goldmine for instructors and coaches in political speeches and debates. Sometimes these provide timeless examples of what not to do, others show us that even with a textbook perfect speech, your campaign still might fail somewhere down the line.

We also sample TED talks and their progeny. Many of them are quite good, teaching us new things and fresh ways of looking at the world. But the TED mandate to leave the audience with a "charge" or "call to action" is often tacked onto a perfectly wonderful informative speech, and I am often left wondering why sharing information and insight with the audience is not enough of a gift in itself.

And then there is a pervasive TED delivery style: techniques and strategies that get used over and over again because -- well, they work. But when everyone is using the same flavor to spice up their speech it all ends up seeming the same. It becomes familiar, almost bland. Canadian comedian/writer Pat Kelly does a wonderful parody TED talk that hits all the right notes, and has you laughing and cringing at the same time. I just did a TED-style talk (video coming soon!), so I understand the temptation to fall back on the tried-and-true formula. But once you start relying on something so predictable, you dilute its importance. Even if it was once valid or original. Kind of like "passionate" and "passion." Think about it: if there really were as many people who were passionate about saving the planet as you hear on TED talks alone, we would have solved all earth's problems by now.

As I tell my students, there is one surefire way to avoid being a cliché: Don't use them!

What is authentic "authenticity"?

I had to laugh when I read Adam Grant's article in the New York Times last week: "Unless You're Oprah, 'Be Yourself' is Terrible Advice." I have said the same thing to countless clients-- really? Do you truly think "being yourself" is such a good idea? But "authenticity" remains a buzzword. It is almost as if being "authentic" has become a sort of magic wand. Or Holy Grail.

I had to laugh when I read Adam Grant's article in the New York Times last week: "Unless You're Oprah, 'Be Yourself' is Terrible Advice." I have said the same thing to countless clients-- really? Do you truly think "being yourself" is such a good idea? But "authenticity" remains a buzzword. It is almost as if being "authentic" has become a sort of magic wand. Or Holy Grail.

When clients ask me to help them be more authentic, I ask what that means. I receive a wide variety of definitions. So I define it, and we get to work. Actually, I define authentic presence--that confident place where you embody a relaxed energy that gets your message across in a dynamic, memorable way. Because that's what they really want. It's not quite the same thing as "being yourself," especially if you are a "low self-monitor" (as Adam Grant would say) who does not filter much of your inner life.

I teach my clients strategies for recognizing where their presence lies, how to access it, and how to consistently project it. Of course the route to each person's authenticity is specific, but there are some general rules. Practicing proper breathing and posture is essential, as is the understanding that speaking is a physical activity. Then you can get out of your head and into your body, which is where you need to be to convey presence. And when you do that, your authenticity falls into place. You are projecting your best self: in control but not pushy, focused but not self-centered. You are confidently sharing what is important to you with others, yet remain open to their ideas, ready to listen and truly connect.

The opposite of this is false presence. And false presence is pretense. It takes more mental effort to maintain a seamless pretense than most people (professionally-trained actors excluded) are capable of sustaining. And of course, there is the default--no presence--which is what may people project. It's not that they are being inauthentic, it's just that their sense of authenticity is submerged and imperceptible to the listener or audience. The professional term for these people is "boring," and they break the second rule of effective communications (the first is "know your audience," btw).

The good news is that everyone has authentic presence to discover and use. Just don't confuse it with unfiltered bouts of "being yourself."

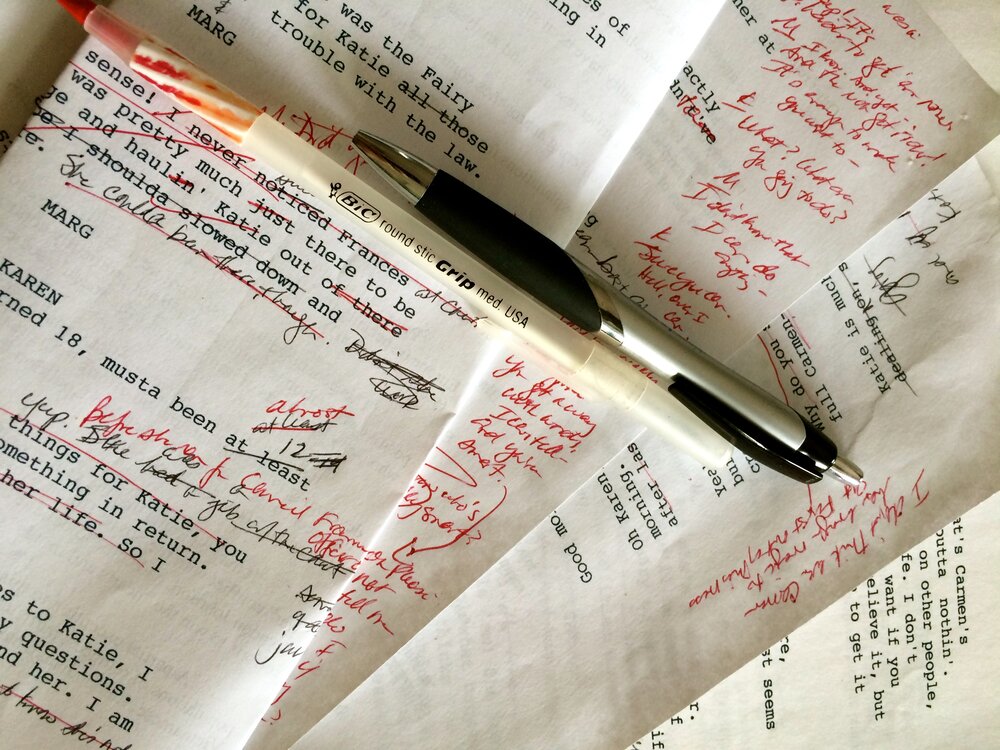

Studying the script

Lately my work has been running along two separate but parallel tracks: coaching clients to be more effective and dynamic speakers who can communicate their authentic leadership, and writing (and rewriting) my latest play. That script is really taking off, and I will blog more about it later on. But for now I wanted to share something that struck me particularly this week as I was toggling back and forth between these two worlds.

In my play, I carefully craft dialogue to reflect what the characters are thinking, and what it is they are trying to communicate, as well as what they are trying to hide. This necessitates being omniscient--knowing what they know, what they are aware of, and what they are unaware of. So, as you can imagine, when my characters speak there is a lot of pausing, as well as unfinished sentences, interrupting, phrases that are imprecise followed by a "you know what I mean." Because on an intimate level, true interpersonal communication happens in the subtext, the feeling underlying what is said and not said. In fact, often the most important words are left unspoken (for a master of this, see anything by playwright Harold Pinter). The playwright uses this tool to reveal that a character is inarticulate, or does not understand, or cannot utter to words because they are too fraught.

All this is to say, though playwrights craft their characters' speech to reveal certain aspects of character to the audience, the characters themselves may be at a loss for words. Or they are speaking spontaneously, reacting to what has been said to them. Often the act of speaking itself is a sort of connection-making that says much more about them and their relationship to their conversation partner than the actual words do. Just like in real life! When we are engaged in private speech, that is.

So when I work with my students and clients on public speaking, I advise them to do the opposite of what my characters do. Since public speech, broadly defined, can be any type of speaking you engage in when you are not with your "nearest and dearest," it cannot be anything like the private speech I conjure up for my characters. In public speech, the words you say matter very much. You cannot afford to be inarticulate, or skirt the issue or leave things unsaid. You can get into huge trouble if you assume the listener can fill in the blanks. You must plan what you need to say, choose the best, clearest, least ambiguous way to say it, and then be ready to listen to what your conversation partner has to say as a way of furthering dialogue. Avoid the very human temptation to slip into the private conversational gambit of impromptu chit-chatting. You will reveal more than you intend!

The soundness of this advice has been proven to me and my clients time and again, and yet it is still occasionally met with resistance. Those who resist are generally the less experienced communicators who know they need help and so come to work with me. The other big bucket of naysayers are old-school top-of-the-heap blowhards who would never work with me in a million years. Somehow, when they find out what I do, they always feel compelled to brag about their excellent, spontaneous, loose, off-the-cuff communications style. They are lousy speakers, but since they are insulated from real scrutiny due to their positions (this is Washington, D.C., after all) no one ever tells them. Perhaps I will put them in a play someday; they are very entertaining!

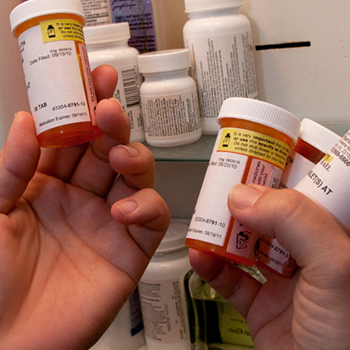

Better living through chemistry?

Recently, I was asked what I thought about the use of beta blockers to relieve speaking anxiety. I have to admit I was taken aback. I've known for a while that these drugs have been used by professional musicians to combat performance anxiety, though that is not a common practice. It is, however, controversial. But I had never been asked about use of these drugs for regular speaking-in-public situations! As someone who helps people overcome "speakers' nerves" on a pretty regular basis, I know that some sort of stage fright is absolutely normal. As a professionally trained actor, I am quite familiar with the concept. Yet I don't think I know any actors who rely on this sort of help. We all get attacks of nerves before going onstage, but part of our training is devoted to developing strategies for working through those anxieties. Most of us use some combination of yoga, breathing exercises, backstage rituals, and of course, rehearsal, to get us where we need to be so we don't keel over when the stage manager calls "places!"

Recently, I was asked what I thought about the use of beta blockers to relieve speaking anxiety. I have to admit I was taken aback. I've known for a while that these drugs have been used by professional musicians to combat performance anxiety, though that is not a common practice. It is, however, controversial. But I had never been asked about use of these drugs for regular speaking-in-public situations! As someone who helps people overcome "speakers' nerves" on a pretty regular basis, I know that some sort of stage fright is absolutely normal. As a professionally trained actor, I am quite familiar with the concept. Yet I don't think I know any actors who rely on this sort of help. We all get attacks of nerves before going onstage, but part of our training is devoted to developing strategies for working through those anxieties. Most of us use some combination of yoga, breathing exercises, backstage rituals, and of course, rehearsal, to get us where we need to be so we don't keel over when the stage manager calls "places!"

It seems a growing number of doctors are prescribing drugs such as propranolol (which treats heart and circulatory conditions) "off label" to patients with speaking anxiety. Before I looked into this, I thought, well maybe this is a relatively harmless little pill, a way to "take the edge off" before a speech. When I looked up propranolol, though, I found it is a pretty heavy-duty drug. If you take it, you have to avoid alcohol, as well as anti-depressants, and NSAIDS (aspirin, ibuprofen, etc). And of course there are side effects! Now, I am sure there may be some people who have such severe anxiety they do need drugs to help with this, but my hope is they are seeing a mental health professional and getting the support they need that way.

I am not a doctor (thought I did play a nurse on TV!), but I do know that if a particular use of a drug is not approved by the FDA there is usually a reason. This article in The Washington Post summarizes the arguments more succinctly than I can. But the bottom line is, feeling nervous when standing before strangers is not a medical "condition." It is a human condition, one that we all feel. Don't fall into the trap of medicalizing something you can train yourself to deal with. People who tell me about their performance anxiety seem to think this is some terrible affliction peculiar to them, when what they describe to me is what any actor feels on preview night.That adrenaline jolt is normal, and useful to an extent. If you have anxiety it means your body is doing what it is supposed to do: reacting to stress. If you want to control the effects of that anxiety, there are plenty of non-pharmaceutical ways to do so--that even allow you to take a celebratory drink after the curtain falls!

Shortchanged by shortcuts

I know my habits are often out of fashion. I am not instant-this or quick-that. And I have never striven to "fail fast." No, my approach to getting things done is more along the lines of "If something is worth doing, it's worth doing well," and "Slow and steady wins the race." So I applauded a story on NPR this weekend giving students a tip for better learning: take your notes by hand rather than typing on a tablet or laptop. The story had a familiar ring to it; I looked it up and recalled reading the article two years ago when it was published in the journal Psychological Science. But the conclusions still stand, and in the period since the science has been done, I am sure thousands of students have migrated from pen-and-paper note-taking to typing. The students who still engage in the former, however, are learning more. Pamela Mueller, one of the researchers, explained it this way in the NPR story, "When people type their notes, they have this tendency to try to take verbatim notes and write down as much of the lecture as they can. The students who were taking longhand notes in our studies were forced to be more selective — because you can't write as fast as you can type. And that extra processing of the material that they were doing benefited them."

I know my habits are often out of fashion. I am not instant-this or quick-that. And I have never striven to "fail fast." No, my approach to getting things done is more along the lines of "If something is worth doing, it's worth doing well," and "Slow and steady wins the race." So I applauded a story on NPR this weekend giving students a tip for better learning: take your notes by hand rather than typing on a tablet or laptop. The story had a familiar ring to it; I looked it up and recalled reading the article two years ago when it was published in the journal Psychological Science. But the conclusions still stand, and in the period since the science has been done, I am sure thousands of students have migrated from pen-and-paper note-taking to typing. The students who still engage in the former, however, are learning more. Pamela Mueller, one of the researchers, explained it this way in the NPR story, "When people type their notes, they have this tendency to try to take verbatim notes and write down as much of the lecture as they can. The students who were taking longhand notes in our studies were forced to be more selective — because you can't write as fast as you can type. And that extra processing of the material that they were doing benefited them."

Another article that vindicated my old-school way of doing things appeared in Sunday's New York Times, "Sorry, You Can't Speed Read." I have always been a fairly fast reader, but never for a second desired to become a lightening-fast one, even though many people have said it has increased their productivity. In this article Jeffrey M. Zacks and Rebecca Treiman conclude that in mastering the technique used in speed-reading (gathering lots of visual information quickly), language comprehension suffers. I relish losing myself in a good story, or teasing out the strands of an author's argument, so I don't like to rush. But if I do speed through the last two pages of a chapter--if I am keeping someone waiting, for example--I have to go back and reread them. Why do I even bother? As Zacks and Treiman note in their op-ed, "If you want to improve your reading speed, your best bet — as old-fashioned as it sounds — is to read a wide variety of written material and to expand your vocabulary."

Old-fashioned. Yep. That's why I also insist my clients practice their speeches for best results. More than once or twice. In an insta-world where easy gratification all too often comes at the speed of light (or pressing of a button), there are some processes where short cuts just don't cut it. Like fast fashion or disposable decor, shortcuts to effective communication result in messaging that is "here today, gone tomorrow." If you want anything to stick--lessons learned, books read, or speeches delivered--you just have to put in the time.

Illustration: "Sea Tortoises Coming Ashore by Night" by Charles Livingston Bull,

courtesy Library of Congress

Seriously not a circus

For many of us who live in metro Washington, politics is a theme that runs through our daily lives. As a communications professional, I have coached people seeking elected office and those who lobby them when they win. And I know that the folks who "run Washington" are not a unique breed of power-crazed maniacs. They are pretty normal people, as variable as the rest of us. Perhaps a few let their lust for power interfere with their better judgement, but the vast majority are not Frank Underwood.

For many of us who live in metro Washington, politics is a theme that runs through our daily lives. As a communications professional, I have coached people seeking elected office and those who lobby them when they win. And I know that the folks who "run Washington" are not a unique breed of power-crazed maniacs. They are pretty normal people, as variable as the rest of us. Perhaps a few let their lust for power interfere with their better judgement, but the vast majority are not Frank Underwood.

But when I look at the current presidential race, I am dumbstruck by the enormous exhibition of ego that is Donald Trump. When I lived in New York in the '80's, I enjoyed following his exploits in Spy magazine. I thought he was yesterday's news. How wrong I was! He has proven to be a celebrity master of reinvention to rival the Material Girl herself.

When people ask my professional opinion, I tell them Trump is a terrible communicator. That's usually no surprise. But if they want details I point out how he deviates from accepted guidelines for good speaking: he is not prepared; he does not engage in active listening; he does provoke for the sake of provocation; he has little respect for his audience. He fails completely at connecting with objective reporters and unsycophantic interviewers. But—I hate to admit it—Trump is highly successful at one thing: when it comes to his supporters, he knows his audience! He has a showman's instinct for giving them what they want, and he throws them red meat with wild abandon. He has built a successful campaign by "playing to the cheap seats," as we say in show-biz. He was the joke of summer who turned into the Great American Reality Star, and his campaign has filled a unique niche in this season's entertainment schedule.

In a couple of months I will be teaching "Speaking for Impact" to high school students as part of Discover the World of Communication at American University. I know as soon as I mention the 2016 election, Trump's name will come up. I will point out the numerous ways Trump fell short of looking and sounding like a leader. But I also will welcome the opportunity to segue from discussing the ethics of public speaking to a larger examination of civic responsibility. Though the specter of Trump in the White House is diminishing daily, he leaves us with a powerful, teachable moment. And a warning of what can happen when people stop paying attention and sit back to enjoy the show.

illustration from "The Circus Procession," published by McLoughlin Brothers, Inc., 1888

courtesy Library of Congress

Metering your thoughts

I have such wonderful clients: they are smart, self-aware people. They know what they know—many are experts in their field—but they are also clear-eyed enough to know what they don't know. And when they know they are not speaking or presenting as well as they should, they come to me. I help them improve their communications skills so they can clearly convey their (sometimes complicated, often paradigm-shifting) ideas to others.

I have such wonderful clients: they are smart, self-aware people. They know what they know—many are experts in their field—but they are also clear-eyed enough to know what they don't know. And when they know they are not speaking or presenting as well as they should, they come to me. I help them improve their communications skills so they can clearly convey their (sometimes complicated, often paradigm-shifting) ideas to others.

Lately it seems a lot of my clients have the same problem: they get stuck in their heads. I don't mean they listen to negative self-talk that holds them back. That is true of every single person I have ever coached, and I always address it by giving my clients strategies for putting that self-talk "out of mind." No, the "stuckness" I am focusing on happens when you are called upon to speak in a meeting and your thoughts come so fast it's hard to get them out coherently. All the right ideas are in there, in your mind, but there is a traffic jam as they try to take the exit ramp.

It is frustrating, yes, to know you actually have the answers, but cannot express them with the dynamic confidence you want. It would be nice if you could just flip a switch and slow your thoughts down so they come to you in a manner that is easier to process. If you were actually in traffic, you'd find the exit ramp meter most helpful. Sadly, our minds are not that automated.

So here's the next best thing: slow down. Breathe before you begin to speak. Put a period at the end of each sentence. Complete each thought. Give yourself a little space between the idea you just verbalized and the next one. Space to breathe. Space to think. Try this until the run-on-tumbling-out-of-words becomes a series of sentences, and you will find you have slowed down your pace to a tempo you can control. Then you'll be able to shape your responses in a way that reflects your expertise and knowledge. And an added bonus: you will have time to gauge the level of audience comprehension, so what you say will land with maximum impact and effectiveness.

It's like your Driver's Ed teacher said: Obey the traffic signals, take your time, and you'll not only have a safer trip, you'll enjoy it more, too.